Nutrition and training around your menstrual cycle is a trending topic in the media. Can we have cycle syncing workouts or a cycle syncing diet? Caution should be taken when interpreting this information and incorporating such recommendations into your own lifestyle as it is based on very little science. Currently, limited research exists to advise individuals on whether our diet and training need to change depending on each stage of the menstrual cycle. Nonetheless, as there is a growing interest in how the menstrual cycle affects appetite, energy intake, sports performance, and more, this article will discuss the research available and provide recommendations that can be made accordingly. This article also aims to avoid the pseudoscience surrounding this trending topic of ‘cycle syncing workouts’ and ‘cycle syncing diet’ to better inform you on how the menstrual cycle may affect your diet, training, and overall results. Doing so will allow you to recognize and monitor your symptoms and tailor your plans, whilst accounting for how you feel.

The Menstrual Cycle

Your cycle length is the number of days from day 1 of your period to the start of the next period. Typically, the start of the cycle is day 1 of your period, and day 28 is the end of the cycle before your next period begins. However, your cycle length can vary; it can be anywhere between 21 to 35 days, and this is considered ‘normal.’ Furthermore, your menstrual cycle can be split into 2 main phases- the follicular and luteal phases. The follicular phase is characterized by shedding of the uterus lining, i.e., your period, which is typically a duration of 3-8 days. After your period, the luteal phase begins and this is characterized by ovulation, which is when an egg is released. This is usually 14 days long, but again this varies, mainly depending on when ovulation occurs. This phase also prepares the body for pregnancy if an egg is fertilized or the start of the next cycle if pregnancy doesn’t occur (4).

Hormonal Changes During Your Menstrual Cycle

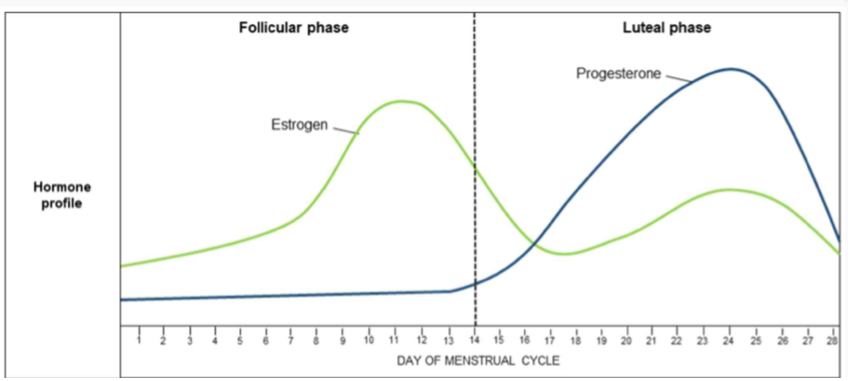

Throughout the entire cycle, hormonal changes occur. Basically, sex hormones act as chemical messengers and elicit changes in the body. The main hormones involved in the menstrual cycle are oestrogen and progesterone, as shown in the figure below.

During menstruation i.e., your period, both hormone levels are low. During the follicular phase i.e., the first half of the cycle and the days between day 1 of your period and ovulation, oestrogen levels start increasing. Then a few days before ovulation, oestrogen levels peak and levels fall back throughout this stage. Oestrogen levels increase again in the mid-luteal phase as the body prepares for a possible pregnancy, then can decrease to low levels during your period again. Progesterone levels are low in the follicular phase, increase towards the start of the luteal phase and reach peak levels in the mid-luteal phase. Levels decrease once your next period starts (7).

This overview of cycle duration and hormonal changes is simplistic and there is still a lot more to discover. The constant changes that occur during the menstrual cycle have triggered interest in knowing how this may impact measures such as energy intake, energy expenditure, performance, mood and more.

How can the Menstrual Cycle affect diet?

How does the menstrual cycle affect diet and whether one can have a cycle syncing diet?

Energy Intake

Energy intake throughout the cycle can vary. Most studies investigating this showed that individuals had significantly higher energy intakes in the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase and this increase in energy intake was shown to be between 90-500 extra calories per day in this phase. This means individuals seemed to eat more in the 2nd phase of the menstrual cycle i.e., around 2 weeks before their period by 90-500 calories per day (6).

However, this is not the case for everyone; another study showed that those that suffer from premenstrual syndrome (PMS) i.e., higher than average fluid retention, depression, irritability, and lethargy, demonstrated significantly increased carbohydrate and calorie intakes in the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase. Conversely, this was not seen for individuals who did not suffer from PMS (9). This again highlights how your experience is very individual to you.

Food Cravings

From the limited available research we have, there have been suggestions that our cravings may be impacted as well. Research has highlighted that we may crave sweets, chocolates, and salty flavors most in the luteal phase (10). This drive for these types of food may be related to brain activity. It has been suggested that the balance between the emotional and logical parts of the brain show greater activity by visuals of high-calorie food compared to low-calorie food and this is especially apparent in the luteal phase (8).

Energy Expenditure

Energy expenditure (EE) i.e., the calories you burn, may be impacted by the menstrual cycle, particularly resting metabolic rate (RMR). RMR is one component of EE and makes up ~70% of your total calorie burn, therefore it is of great interest. It is the calories you burn to maintain basic body functions while at rest e.g., breathing, and circulation.

Some research exists that shows RMR may increase in the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase (1). Once again, this information may not be the same for every female as results in this area are still mixed and there is a need for larger and higher quality study designs to better guide the general population.

Bloating

Individuals may also experience bloating during their cycle, and this can be uncomfortable, but this is completely normal if physicians have ruled out GI issues such as IBS. Evidence from a study looking at body weight changes throughout the menstrual cycle showed that body weight tends to be lower during ovulation i.e., mid-part of the cycle, and increases during the luteal phase (13).

Bringing awareness to what and when you experience such symptoms allows you to gain a more positive perspective on your health and fitness journey. So, the next time you crave a high-calorie food, eat more, and experience bloating towards the end of your menstrual cycle, you know why and understand that there is more happening that you may not see such as a potential increase in your RMR. Hence, it is important to minimize such distractions so that you can enjoy the journey and be consistent- this is what truly matters.

The impact of the menstrual cycle on exercise

A recent article found that across 5 studies, most athletes perceived that their performances were affected by their menstrual cycle, which includes strength, speed, and power. Most highlighted that the late luteal and early follicular phases i.e., ~1 week before and during their period, was when their performance was most impacted. They perceived feelings of lethargy, fatigue, and menstrual pains as potentially affecting their performance.

However, looking at the research deeper, those perceptions and/or feelings were not translated to any reduction in performance compared to other phases in their menstrual cycle. Another meta-analysis mentioned that these differences were so small that they are termed insignificant and hence guidelines on exercise performance during different phases of the menstrual cycle or cycle syncing workouts cannot be recommended to the general population and athletes at this time (5,3).

Consequently, recommendations should be individualized on each person’s response to exercise performance during different menstrual cycle phases. This basically also tells us, considering the lack of evidence on this topic, perception and actual exercise performance may not always be associated with each other; you can feel amazing, but perform worse than expected and vice versa.

Can we have Cycle Syncing Workouts or Cycle Syncing Diet?

Considering the lack of evidence, it seems meaningless to attempt to prescribe workouts according to your menstrual cycle phase, yet a trending topic of concern is ‘cycle syncing workouts and diet,’ which attempts to do just that.

Cycle syncing was a term that a Functional Nutritionist called Alisa Vitti came up, who also founded the popular menstrual cycle application Flo (11). However, this idea as you’ve seen the overall evidence and research have been weak. Essentially, we should account that this concept of ‘cycle syncing workouts’ and ‘cycle syncing diet’ has not been tested for health using high-quality studies, and research on performance is still in the early stages. Nonetheless, this trend of ‘cycle syncing workouts’ or ‘cycle syncing diet’ is currently gaining popularity on different social platforms such as YouTube, Tik Tok, and others.

Adding to the recommendations of using an individualized approach, researchers tracking people’s mood to see how it changes throughout their menstrual cycle found that every individual had a consistent pattern of change throughout their cycle and this pattern of change couldn’t be compared to others (11). Accordingly, we should be looking at individual patterns of change and not an average pattern of change for all individuals.

Another review also looked at perceptual responses and found some differences across the menstrual cycle phases, specifically competitiveness and motivation were better compared to luteal and follicular phases. On the other hand, mood disturbance and menstrual symptoms were worse during pre-menstruation and during menstruation compared to the luteal phase and ovulation.

However, it is important to note that the different methods used in the studies limit the extent to which these results can be generalized and so more research is needed (12). Therefore, it is vital to guide individuals to listen to their bodies rather than following general advice on how to structure their workouts.

Takeaways

You may feel different across your menstrual cycle and these feelings can vary from person to person.

There isn’t much research on training according to your menstrual cycle phase, therefore generic advice and recommendations on ‘cycle syncing workouts’ or ‘cycle syncing diet’ cannot be made right now.

Consult registered dieticians/nutritionists and/or physicians who specialize in this field to ensure an individualized recommendation can be made for you.

Lastly…

It is important to listen to your body- using tracking applications (flo, clue, etc.) for your menstrual cycle can help you monitor how you feel, and you can start tracking this i.e., study yourself!

Sources

1.Benton, M., Hutchins, A. and Dawes, J., 2020. Effect of menstrual cycle on resting metabolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, 15(7), p.e0236025.

2.Bernhardt, S., Dasari, P., Walsh, D., Townsend, A., Price, T. and Ingman, W., 2020. Timing of breast cancer surgery during the menstrual cycle‑is there an optimal time of the month? (Review). Oncology Letters, 20(3), pp.2045-2057.

3.Blagrove, R., Bruinvels, G. and Pedlar, C., 2020. Variations in strength-related measures during the menstrual cycle in eumenorrheic women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 23(12), pp.1220-1227.

4.Bull, J., Rowland, S., Scherwitzl, E., Scherwitzl, R., Danielsson, K. and Harper, J., 2019. Real-world menstrual cycle characteristics of more than 600,000 menstrual cycles. npj Digital Medicine, 2(1).

5.Carmichael, M., Thomson, R., Moran, L. and Wycherley, T., 2021. The Impact of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Athletes’ Performance: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), p.1667.

6.Davidsen, L., Vistisen, B. and Astrup, A., 2007. Impact of the menstrual cycle on determinants of energy balance: a putative role in weight loss attempts. International Journal of Obesity, 31(12), pp.1777-1785.

7.Draper, C., Duisters, K., Weger, B., Chakrabarti, A., Harms, A., Brennan, L., Hankemeier, T., Goulet, L., Konz, T., Martin, F., Moco, S. and van der Greef, J., 2018. Menstrual cycle rhythmicity: metabolic patterns in healthy women. Scientific Reports, 8(1).

8.Frank, T., Kim, G., Krzemien, A. and Van Vugt, D., 2010. Effect of menstrual cycle phase on corticolimbic brain activation by visual food cues. Brain Research, 1363, pp.81-92.

9.Gallon, C., Ferreira, C., Henz, A., Oderich, C., Conzatti, M., Ritondale Sodré de Castro, J., Parmegiani Jahn, M., da Silva, K. and Wender, M., 2022. Leptin, ghrelin, & insulin levels and food intake in premenstrual syndrome: A case-control study. Appetite, 168, p.105750.

10.Gorczyca, A., Sjaarda, L., Mitchell, E., Perkins, N., Schliep, K., Wactawski-Wende, J. and Mumford, S., 2015. Changes in macronutrient, micronutrient, and food group intakes throughout the menstrual cycle in healthy, premenopausal women. European Journal of Nutrition, 55(3), pp.1181-1188.

11.Lorenz, T., Gesselman, A. and Vitzthum, V., 2017. Variance in Mood Symptoms Across Menstrual Cycles: Implications for Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. Women’s Reproductive Health, 4(2), pp.77-88.

12.Paludo, A., Paravlic, A., Dvořáková, K. and Gimunová, M., 2022. The Effect of Menstrual Cycle on Perceptual Responses in Athletes: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13.

13.White, C., Hitchcock, C., Vigna, Y. and Prior, J., 2011. Fluid Retention over the Menstrual Cycle: 1-Year Data from the Prospective Ovulation Cohort. Obstetrics and Gynecology International, 2011, pp.1-7.

Lana El Halteh is pursuing MSc Clinical Nutrition from the University of Aberdeen, UK and working towards becoming AfN (Association for Nutrition, UK), registered as an Associate Nutritionist and getting her Nutrition license in Qatar. She is also SENr (Sports and Exercise Nutrition Register, UK) graduate registered and a BSc graduate in Physiology, Sports Science and Nutrition from the University of Glasgow. Instagram- UrbanNutritionbyL.